A WRITING LIFE: PART THREE

by elementor | Sep 23, 2024 | Architecture, Modern life

In 2004 I got a call from Jacob Weisberg, the editor of Slate. Would I be its architecture critic? Sixteen years earlier I had written a column for Wigwag, a short-lived general interest magazine that had been done in by the 1991 recession. But I was now 61, which seemed a bit old for an online magazine that appeared to be staffed by twenty somethings. I told Jacob that if I accepted I was not interested in simply reviewing new buildings. He said that was fine with him. Over the next six years I wrote 133 essays and slide shows. “Supersize My House,” “Don’t Count Your Titanium Eggs Before They’re Hatched,” and my favorite, “Tall Buildings, Short Architects.”

A WRITING LIFE: PART TWO

by elementor | Sep 16, 2024 | Architecture, Modern life

In 1989, three books later, I wrote The Most Beautiful House in the World, about how my wife Shirley and I built our own house in rural Quebec. The book was reviewed on the front page of the New York Times Book Review, and made it to the bestseller list. Later that year I got a call from a Times editor who invited me to write something on architecture for the Arts & Leisure section of the Sunday paper. I was taken aback because although I was an architect, I had written articles and book reviews on other subjects, but I had never been asked my opinion about architecture. I realized that in America (I was still living in Canada at the time) my successful book meant I was now an expert. I wrote “Architects Must Listen to the Melody.” It began, “Goethe once described architecture as frozen music; if he was right, could cities be described as congealed concertos?”

A WRITING LIFE: PART ONE

by elementor | Sep 13, 2024 | Modern life

In the 1970s I belonged to the Minimum Cost Housing Group at McGill University in Montreal. Our research included third world slums, alternative technology, composting toilets, well, that was the seventies. We published and sold booklets—Stop the Five Gallon Flush was the most successful. Around 1978 I thought it would be a good idea to combine all the publications in a book—after all, this was the era of the Whole Earth Catalog and the Domebook. I didn’t have much success finding a trade publisher. I did get one positive response from Bill Strachan, a Doubleday editor. He was not keen about my proposal, but he had read a short article of mine in Stewart Brand’s little magazine, CoEvolution Quarterly. Would I consider expanding my article into a book, he asked? Why not, I thought. Paper Heroes: A Review of Appropriate Technology was my first book. (The jacket above is from the 1991 Penguin edition.)

OPEN BUILDING

by elementor | Aug 30, 2024 | Architecture

My friend Steve Kendall gave me a copy of his latest book, written with the late John Habraken, Open Building for Architects. Wiki defines Open Building as “an approach to the design of buildings that takes account of the possible need to change or adapt the building during its lifetime.” Reflecting on this ambitious goal—buildings can last for centuries—led me to a conclusion: There’s no such thing as Open Building. Or, to put it another way, buildings have always been open to change.

I am put in mind of the Uffizi Museum (originally magistrates’ offices), the Louvre, the Hermitage, the Belvedere (originally royal and imperial palaces), the Tate Modern (originally a power station), the Musée d’Orsay (originally a railway terminal), the National Portrait Gallery (originally the Patent Office), and the Prado (originally designed as a science museum). Of course, these are all famous museums, but Europe is full of palazzos, mansions, and hôtels, that have found second and third lives in a variety of altered uses.

Closer to home, consider building change in my city, Philadelphia. Innumerable row houses have been converted to non-residential uses, innumerable industrial lofts repurposed to residential use, mansions turned into multi-family apartments, the city’s school board headquarters converted to residential use, and a downtown hospital turned into apartments. And that’s only the residential conversions. Across the street from me is a juvenile court and jail that has been converted to office use, Alexander Hamilton’s Second Bank of the United States is now an art gallery, the Philadelphia Museum of Art has converted an Art Deco insurance company building into a museum wing, a pumping station has become a theater, two Art Moderne office towers and a YMCA are now hotels, and the venerable Reading Terminal now functions as part of a convention center (see above).

While none of these buildings was designed for such unpredictable change (how could they have been? that’s the definition of unpredictable), changes did occur and were accommodated. Perhaps it could have been done more efficiently, but could future functional demands and future technology really have been predicted a hundred years in advance? I think not.

The truth is that buildings have always been open to change—they had no choice.

GOD-KNOWS-WHAT-KIND-OF-CLASSIC

by elementor | Aug 18, 2024 | Architecture

I read Catesby Leigh’s interesting article, “Uncle Sam’s Buildings,” in The American Conservative. He argues in favor of the federal buildings that were built in the prewar era, and which more or less followed the classical style, and is critical of the modernist era, perhaps best characterized by the awful FBI headquarters building in DC. His essay brought up a question for me. The examples of classical federal buildings that he admires are all from a particular era, and his essay implies that this architectural style should continue ad infinitum. Whatever the merits of this suggestion, it does fly in the face of all we know about history. Architecture has never stood still: Bramante was followed by Bernini, then Wren, then Edwin Lutyens, then Paul Cret. There are many examples of federal buildings of the 1930s (which Leigh conveniently ignores), that represent a different sort of traditional approach: in my city, Philadelphia, Rankin & Kellog’s main post office across from 30th Street Station (illustrated above), and Harry Sternfield’s Nix federal courthouse and post office; in DC, Cret’s Federal Reserve Board Building, and Bertram Goodhue’s National Academy of Sciences on the National Mall. None of these architects used the usual paraphernalia of Beaux-Arts classicism, yet their work is clearly not “modernist.” Would you call it classical? Not exactly; at the time some people called it Moderne. Goodhue, who resisted suggestions by the Commission of Fine Arts to add a colonnade, called his design “God-knows-what-kind-of-Classic.”

Leigh mentions President Trump’s 2020 executive order stipulating that classical and traditional architecture be given priority in large federal buildings. I think that the intense negative reaction to the executive order, apart from the fact that it came from Trump, had to do with the retrograde image of “buildings with columns.” Yet, as recent history shows, this is by no means the only alternative.

PHILADELPHIA ON THE ROCKS

by elementor | Aug 17, 2024 | Architecture

A happy four days spent on Mount Desert Island. Gave a lecture on Planting Fields to the Beatrix Farrand Society; visited the spectacular Abby Rockefeller Garden; had a memorable lunch at Martha Stewart’s great house, Skylands; saw a beautiful wooden body 1913 Peugeot in the Seal Cove Auto Museum; went sailing on a Herreshoff canoe yawl; ate Scott Koniecko’s perfect oysters in his as-yet unfinished perfect house. I stayed in Northeast Harbor, once known as Philadelphia on the Rocks because so many Philadelphians summered there, and because they were a tipsy crowd. Cheers!

WRITING

by Witold | Jun 25, 2024 | Modern life

In a spirited talk at Purdue University, the noted biographer Stacy Schiff was asked what advice she might give to aspiring writers. “Your only job is to make the reader turn the page,” was one of her answers. Pithy, and true. Years and years ago, before she became a famous biographer, Stacy was an assistant editor at Viking, my editor when I was writing Home. Later, when I was setting out to write a biography of Frederick Law Olmsted I too asked her for advice. “You need to learn everything about your subject,” she counseled, “but the reader doesn’t need to know everything you know.” Equally good advice, and not just for biographers.

ARCHITECTURE AND BUILDING

by Witold | May 13, 2024 | Architecture

“It is very necessary, in the outset of all inquiry, to distinguish carefully between Architecture and Building,” wrote John Ruskin in the opening chapter of The Seven Lamps of Architecture. The modern democratic spirit tends to resist this distinction. Surely all buildings can be architecture, the humble as well as the grand, the cottage as well as the cathedral? The problem with this well-meaning leveling out is not that it elevates the former but that it tends to lower the latter. When a utilitarian apartment block or office building is treated as architecture, that establishes a sort of benchmark in which repetition, functionality, and practicality become preeminent architectural virtues. What then is to distinguish the civic or religious monument? “Nothing” said Mies van der Rohe, whose severe logic required him to use a similar architectural language for both the chapel (above) and the heating plant at IIT. Less doctrinaire early twentieth century architects, who found themselves obliged to design both office buildings and cathedrals, remained cognizant of the difference. Their commonsense solution was to introduce Architecture piecemeal. A factory building might get a classical entrance portal; a department store display window might warrant a special surround. In an office tower, the Architecture might be limited to the lower two floors, or the lobby, while the upper floors were left plain, whereas a more significant building, a public library or a concert hall, would get wall-to-wall treatment. It still seems like a useful compromise.

PARK BENCHES

by Witold | May 12, 2024 | Design

When I wrote Now I Sit Me Down, a history of chairs and sitting, I included folding chairs, office chairs, and chairs on wheels, but I neglected park benches. I suppose I took them for granted. Whenever I go for a walk I often sit down on a park bench. They’re usually not very comfortable. Some are made out of heavy slabs of wood, to reduce maintenance, I suppose; more modern benches seem to be designed mainly to discourage loafing. As with much sitting furniture, you have to go back in time to find an exemplary design, in the case of benches, to mid-nineteenth century Paris. Jean-Antoine-Gabriel Davioud (1824-1881) was a prize-winning graduate of the École des Beaux-Arts who worked for the Paris planning department at the time that Baron Haussmann was remaking the city. Davioud designed fountains, arches, and gates, as well as those characteristic advertising columns plastered with posters that you can still see on Parisian boulevards. He was also responsible for two types of benches: the banc droit, or upright bench, a simple two-way facing bench with a shared back, and his wonderfully designed banc gondole. The gondola bench is made of thin wooden strips supported by cast iron frames. The ergonomic profile forms a sort of S-shape, with sinuous curves at the front and rear. Claude Monet painted his wife, Camille, sitting on a gondola bench in 1873 (not in a park, but in their garden at Argenteuil). No one has improved on Davioud’s design since.

SKETCHING

by Witold | May 5, 2024 | Architecture, Landscape architecture

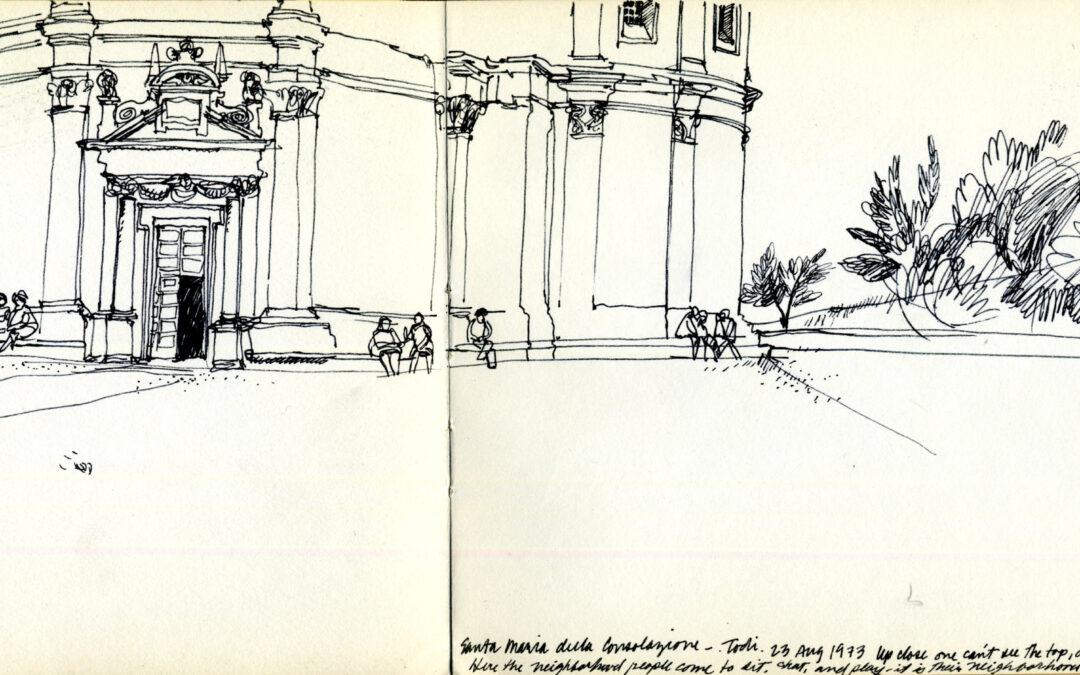

Architects have always travelled with sketchbook in hand. Partly it’s a way of recording interesting places, but more importantly, it’s a way of seeing. The opposite of point-and-shoot, sitting and drawing is a leisurely way to absorb one’s surroundings. My friend Laurie Olin, a lifelong travel sketcher, has been publishing collections of his sketches, grouped by country; four years ago France Sketchbooks and recently In Italy, both from ORO Editions. Olin’s sketches are more than attractive impressions—although they are that—they also reflect a landscape architect’s practiced eye, being full of detailed notes and observations. What also struck me is how his sketches are often populated, like the church of Santa Maria della Consolazione in Todi (above). This sets him apart from most architects who tend to record buildings and spaces but not the life they contain. In Olin’s sketch, the sixteenth-century church, which had many architects, including Bramante, Sangallo, and Vignola, becomes a classical backdrop for groups of sitters, and for a mother and child and their little dog.

THE LATEST

Coming October 8